One of the best parts of travelling abroad is knowing the indigenous people of the area. When it comes to Iran, going deep into Nomad tribes of Iran, and it’s almost like traveling back into the past. Some of these indigenous people still follow the same life of their ancestors; moving twice a year with their herds in Zagros mountain ranges in search of grass. Here you find yourself back to nature among primitive nomadic tribes with their unique cultures & customs. Each Nomad tribes has its own principles considering every aspect of their lives. Some of these tribes are migrants Nomads, some half-migrants and the rest are settled

In less than a month, Nomads are going to move back to the lower altitude of Mt. Zagros where they began their spring migration (Kuch) four months ago. Back then, the majority of people were nomads and each belonged to one main nomadic tribe. So, at times of Kuch, each family followed his own tribe. Usually, brothers & cousins moved together. Now in this article, first, you are going to know about different types of Iran Nomad Tribes, and then you will read more specifically about Bakhtiari Nomads.

Nomad Tribes of Iran

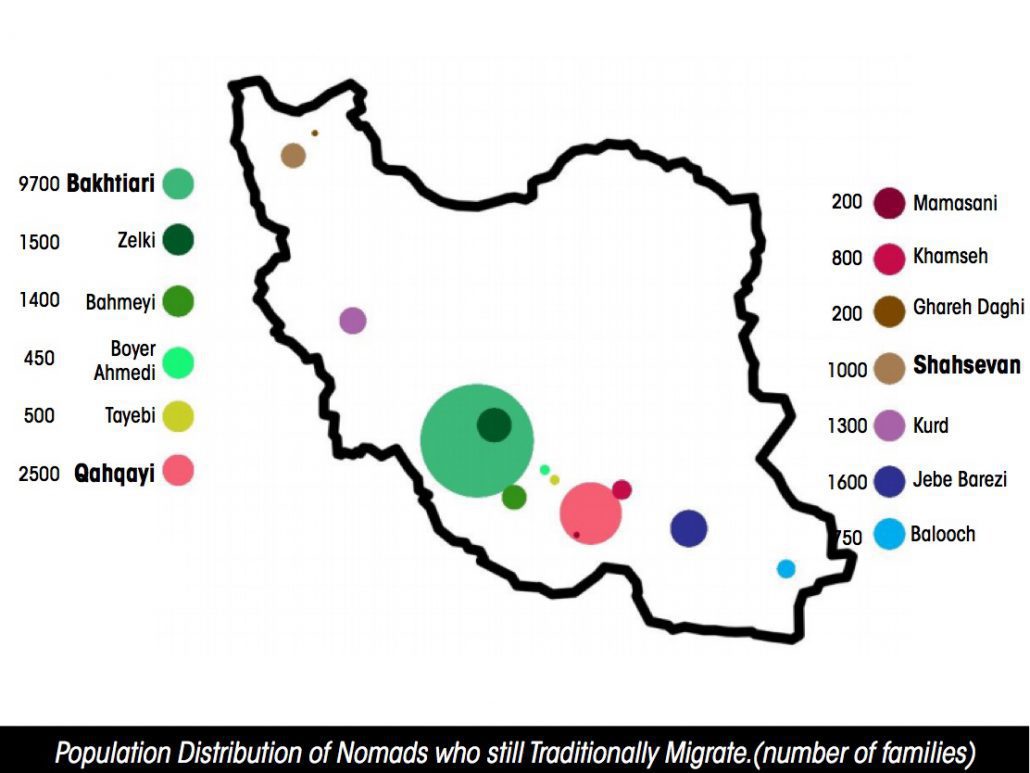

Tribe refers to a group of families who have a feeling of community. Members of a tribe occupy a common territory and follow similar customs. The term may refer to a group of primitive people and families who do transhumance together. It is so common among the people of a tribe to visit one another, intermarry, and meet together for major religious ceremonies. They have a common dialect and customs. Iran has many nomadic tribes. Nomadic tribes[2] of Iran are of two types considering their numbers: Large tribes & small tribes.

Large Tribes

The first group of nomad tribes of Iran is the large tribes. These Nomads also differ in many respects. They are of three groups:

- Like Bakhtiari Nomads: They are always on the move, and more than 80% of them do seasonal transhumance/migration (Kuch). They always pass through the ancient nomadic paths, and every year in their winter pastures (qishlaq), they stay in the same spots.

- Like Boyer Ahmad Nomads: A small number of them live in their summer pastures (Yaylaq), while a large number of them are in winter pastures. More than half of them are moving nomads, who do seasonal transhumance.

- Like Torkaman Nomads: They are settled down and no longer move between pastures. But they move their flocks of goats and sheep in surrounding pastures.

Small Tribes

The second group of nomad tribes is the smaller tribes. In the past, since these small tribes were in danger of being attacked by the larger tribes, they chose to be settled down. Nowadays, many of them are trying moving with their herds (transhumance) again, because they believe ‘Kuch’ is the very epitome of the nomadic lifestyle.

Bakhtiari Nomads: The Biggest Nomad Tribe

There are not so many historical documents about Iran Nomads, and our only document of these indigenous people of Iran is about their political & martial arrangements. These wandering and roaming people mostly have no fixed habitations and are mostly pastoral. They practice transhumance which is proved to be vital for the preservation of nature. But who are Bakhtiari Nomads?

Who are Bakhtiari Nomads?

Bakhtiari tribe or ‘the great Lor’ is one of the most important nomad tribes of Iran. Their territory, known as ‘Bakhtiari Land’, is located in an area between Isfahan and Khuzestan. Mt. Zagros ranges pass through their land, diving it into two geographical regions; mountainous regions in the east, and flats in the west. The mountainous regions are Bakhtiaris’ summer pastures, and the plains and flats are their winter pastures.

They are estimated to be around 500000 people, living in an area of 7500 km. 40% of them (200000) are nomads and semi-nomads who move between summer and winter pastures. They are herdsmen with herds of sheep and goats.

They are of two main groups; ‘Haft-Lang’ and ‘Chahar-Lang’. Each has its own territory. The former move to eastern parts of Khuzestan, such as Andika, Masjed Soleiman, Shooshtar, Izeh, Shahrekord, and Brojen in Chahar-Mahal Bakhtiari.

The latter moves mostly between Dezful and Izeh in Khuzestan, or Daran in Isfahan, and Aligodarz and Brojerd in Lorestan.

He has always been a nomad

Bakhtiari Nomads’ Summer & Winter Pastures

Their summer pastures are in Isfahan’s western highlands. The highest mountain in the area is 4549 m. The winter pastures are in eastern parts of Zagros ranges, and it continues to some parts of Khuzestan province.

Bakhtiari Nomads’ Kuch (Transhumance)

Bakhtiari Nomads do their seasonal transhumance twice a year in spring and autumn from mountains to fields and vice versa. Early in spring, they move from winter pastures to summer pastures, and in autumn they move back. The distance between the two locations is different among different tribes, but it is about 300 km, which takes 10 to 15 days.

Kuch is typical among the nomads, and it happens every year on a regular basis. Each tribe takes the same route each year, and they have their own summer pastures in which no other tribe can stay. Next year again, they set up their tents in the same spot.

Despite all the difficulties, they enjoy their transhumance, and they have so many happy memories of their epic Kuch. Kuch is the typical and unique feature of the nomads. Those who have big flocks are the wealthy ones who have more facilities while they are moving in mountains and pastures, and usually, they choose the longer routes. On the other hand, the less fortunate ones often postpone their transhumance, and they choose the shorter routes.

Nomad’s Daily Shares of Chores

In a nomad family, everybody has her/his own shares of chores. Age and sex are two important factors in assigning the family members their tasks. So, men’s responsibilities are different from women, and children from grown-ups. But there are some works done by both men and women.

Chores done by women are: domestic chores; cooking, washing the dishes, milking, making dairy products, weaving Jajims, carpets, and black tent, fetching water from springs, taking care of the children. They sometimes do shepherding. In the time of kuch, women play an important role in gathering up the things and tent and loading the mules. Men also help them to pack on the day of kuch.

Chores done by men: Men are responsible for economic and political tasks. Dealing with other tribes’ main members and Kalantars, guarding the herd, commuting to villages and cities and doing commerce. When the father is away, the older son does his responsibilities. Farming, renting lands, working in other nomads’ fields are some of their tasks.

It is not common among nomad men to do weaving and knitting. But in some tribes, men also help the women in making Choqa & Jajim.

Chores are done by children: children have a leading role in shepherding and milking the flock. The main shepherd of the flock is always a man since it starts early in the morning till the evening. As the father of a nomad family has some other tasks to take care of, most of the time the sons do shepherding. Children also have their own small flocks of lambs. In nomad families, children learn about their share of responsibilities from childhood. Boys do after their fathers, and girls follow their mothers.

Packing the mules to move from winter pastures to summer pastures in Mt. Zagros

Marriage in Nomad Tribes

Intermarriage is so common among nomad tribes of Iran. They usually get married to someone from their own tribes. They marry early, around fifteen. One of the reasons is the family’s big flocks. Raising big flocks needs more people. The bigger the family, the easier the They make their own clothing for wedding parties and they are mostly light-colored ones.

[2]The common word is “IL” meaning tribe, race, group and a good company